The demands of COVID-19 on healthcare systems requires the whole system to adapt our usual ways of providing care to create capacity to respond.

Things are moving quickly, but at the time of writing the Australian Government has progressed to stage 3 of the Expansion of Telehealth Services plan allowing vulnerable general practitioners and other health professionals to provide care via phone or video under Medicare. Preparations underway to progress to stage 4, at which all patients with or without COVID-19 become eligible to receive care via telehealth from any general practitioner, medical specialist, mental health or allied health professional during the COVID-19 health emergency.

Right now many health services will be scrambling to introduce or quickly scale telehealth as a core part of their care offering, and many may be doing this without the benefit of a Service Designer on staff.

In 2017, I spent a year working with the Royal Children’s Hospital Telehealth Program and their clinical champions to develop a universal framework to fully integrate telehealth into their models of care, enabling any specialist clinic team to quickly identify if an appointment was telehealth suitable or if it required in-person care. I’d like to share with you our approach, what we learned developing it, and how other services can use this as a roadmap to quickly scale their own telehealth services.

Why thinking about models of care matter

In many services, telehealth has been a fringe offering driven by a few passionate early-adopting clinicians who assess suitability on a case-by-case basis, usually for the patients they personally see.

When organisations begin seriously engaging with telehealth, much of the early discussion surrounds technical considerations, setting up cameras, microphones, software and platforms.

When telehealth can be safely and reliably delivered tends to be a more nebulous consideration. It’s a more difficult and nuanced conversation to consider how we might change our collective behaviours, processes, and decision making heuristics, but it’s one that needs to be had in order to make telehealth a sustainable service offering. Attempts to scale telehealth without integration into the model of care leads to inconsistent implementation, patients receiving inadequate care or requiring additional appointments, and clinicians who become frustrated and lose confidence in the approach.

Developing this framework took the best part of a year having nuanced conversations about how care could be adapted along with small and safe iterative tests before we could integrate telehealth as a sustainable part of our service delivery.

In 2018 I presented the approach I developed at the Royal Children’s Hospital to an international audience at the IHI BMJ Quality and Safety in Healthcare Conference. What follows has been updated and adapted to be broadly applicable beyond tertiary specialist clinics as to be more easily translatable into primary care services. In light of the intention to reduce unnecessary face to face contact as much as possible, I have also stripped back much of the discussion and consideration of the benefits of assisted telehealth, in which a local healthcare provider is with the patient during a telehealth consultation with a specialist.

Step 1: Map your current model of care

To begin, you need a shared understanding of how you usually provide face to face care. You’ll want a solid understanding of the patient’s journey through your service, as well as the referral pathway (if your service requires referral in). You will need to involve a representative from each team that is involved in coordinating or delivering care for this service, otherwise you will make assumptions that create difficulties and barriers down the line. It is not uncommon to discover interfaces between these teams that lack clarity, coordination, or ownership within the existing process. Take note of these and do what you can to improve them for the telehealth offering.

Within a single service there can be a multitude of patient journeys. For a quick and dirty scale up, analyse your caseload either by diagnosis or care provided and apply the Pareto principle (~80% of your activity is spent on 20% of diagnoses / types of care), then map these most common models of care. Not all of the points of care within the focal 20% will be suitable for delivery by telehealth, but they are the place to start your inquiry into what is possible.

Step 2: Re-imagine how care could be delivered

Using the patient journey map for a face to face appointment, focus on individual points of care. Ask your team to get creative in laterally exploring how they might approach providing this care if their only option was to communicate by phone or video.

When assessing if a point of care is suitable for remote delivery, there are 3 broad considerations:

The type of care required

- What investigations and treatments are required at this point of care?

- (For services requiring referral) Can these be ordered / performed / trialed by the referring provider prior to this specialist consultation?

- Does this point of care require a clinician to be physically with the patient to perform the required investigations or treatments?

- If so, could this be adequately performed by a family member or caregiver with support / instruction from the healthcare provider?

External constraints

- If the patient is taking part in a clinical trial, does it preclude treatment off-site?

- (Australia specific) Does the patient live in a remote or rural area? If so, they are eligible for care using the usual MBS telehealth items

- (Australia specific) Does the patient and/or provider meet the current requirements for the special COVID-19 MBS telehealth items?

Patient specific considerations

- Is this patient and their family open to using telehealth?

- Does the patient require support services (e.g. interpreter services) to be present during the consultation?

- Does the treating / triaging clinician feel confident that this point of care can be delivered via telehealth for this particular patient?

Consider each point of care on your patient journey maps using these prompts, and decide which of the following categories they best fit:

- Cannot be adequately delivered by telehealth – face to face required

- Can be delivered by telehealth – requires hands on assistance from a carer or family member

- Can be delivered by telehealth – no hands on assistance required.

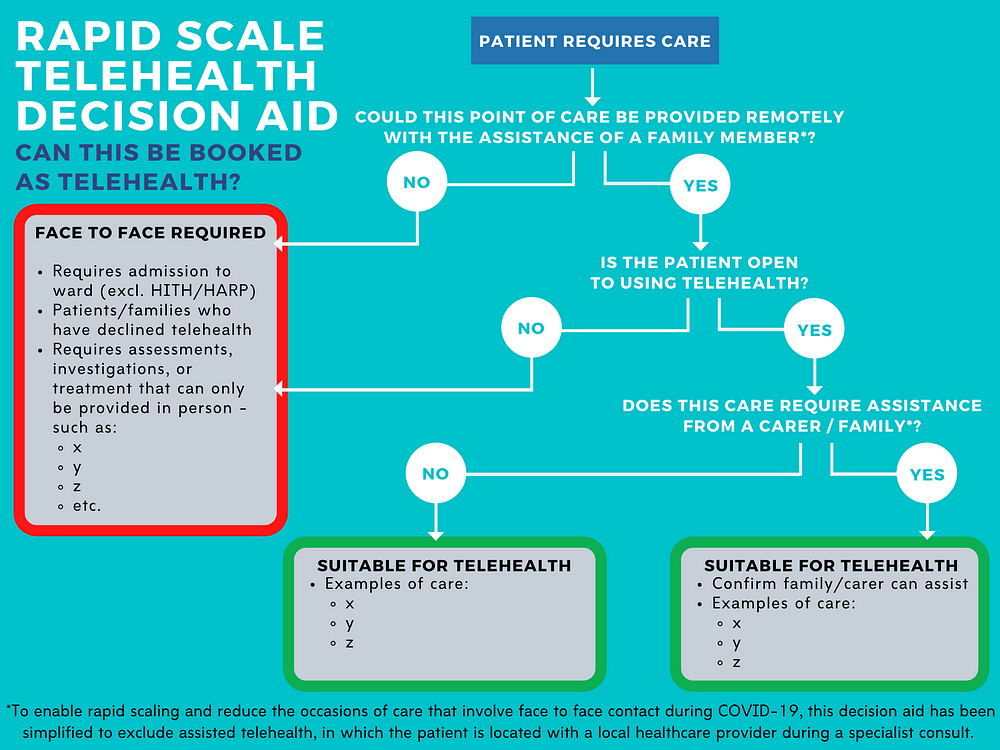

Step 3: Create a decision aid

Creating a shared mental model across your service of what types of care are and are not appropriate for telehealth is key for consistent wide-spread use.

Turn the insights from your re-imagining to create a single page decision aid, including concrete examples of what care is suitable face to face, what care would require hands on support from a family member or carer, and what care can be delivered without additional support.

Sense test these aids with some clinical staff that have not been involved in their development. Socialise the decision aids with all clinicians triaging referrals / appointment requests, and those treating patients who may organise follow-up appointments. Provide copies in all spaces where this work is done.

These decision aids are a simplified model, as such they are only intended as a guide to prompt consideration of telehealth as a viable option and to provide some consistency in the way decisions are made. They do not replace clinical judgement, and ultimately it is the decision of the treating or triaging clinician based on their knowledge of the individual patient and their circumstances.

This simplified decision aid has been adapted for use in this time of rapid scaling and reducing face to face contact where possible. As such, it does not take into consideration assisted telehealth, in which a patient attends an appointment with their local healthcare provider during a telehealth consultation with a specialist. This approach may be beneficial to integrate into your model of care at a later time.

Step 4: Establish process for booking telehealth appointments

Telehealth fails to provide reliable care without robust processes in place to ensure effective communication and hand-offs between teams involved in coordinating care. Early telehealth systems tend to be person-dependent, with poor visibility of what needs to be done to coordinate a call, creating a single point of failure should that person become unwell.

Create a swimlane process map showing the tasks involved, decisions to be made, and hand-offs between teams to clarify roles and information channels and assist with troubleshooting if something goes awry.

If your health service does not have a dedicated Telehealth Coordinator, this is a role worth investing in. A dedicated coordinator instrumental in transitioning telehealth into mainstream practice by supporting patients with test calls, troubleshooting technical issues with clinicians, and further refining your processes. Protect your Telehealth Coordinator from become a single point of failure should they become unwell by having them skill up some clinical and administrative staff to become Telehealth Super Users.

Step 5: Small bets, scaled quickly

Whenever introducing telehealth to a new clinic, new cohort, or new service, start small, learn fast, and scale as you build confidence. Begin with 1 patient, 1 clinician, and 1 point of care. Where possible, include an observer to pay attention to what appears difficult, clunky, or worked around. Afterwards quickly convene to debrief — what went well, what needs work, what was unexpected, and what we might do differently. If confidence has grown through this test, scale up by 5 points of care, and review again. This may feel slow to start, but if you sense and respond well to challenges as they arise you will experience exponential growth.

As your confidence and occasions of service grow, you will need a less resource-intensive way of gathering feedback. Attaching a simple survey to the back of your call, asking people to rate ‘How likely are you to recommend telehealth consultations?’ on a Likert scale followed by ‘Can you tell us why you provided that score?’ will allow you to receive ongoing feedback, identify issues early and respond accordingly.

That’s it.

In a nutshell — 12 months of experimentation, testing, failing, trying again across 5 different clinical areas, then reducing it down to the core elements.

My hope is that by sharing this process and framework at this time, the many other services presently grappling with this challenge can adapt this approach to rapidly scale their own services.